Articles

Blade Runner by Steven Kotler

I read this article some years ago. Was at the barbers, waiting to get a haircut, and Kotler's writing took me back to my teens, living in Ohio, spending lots of nights (and days) at an old repertory cinema. I had a friend who would go with me to midnight showings of Repo Man, Ziggy Stardust, Eraserhead, Blade Runner, and many others. We weren't punks. We were geeks. Often, we'd schedule our lives around the theater's monthly calendar. Kotler captures this cinema-obsessed coming-of-age era, and the resonance of Blade Runner exceptionally well, which is why I asked him if I could re-publish it here. This was originally in the May 2006 edition of Giant Magazine. - Stephen Jared

You Deckard, You Blade Runner: How Ridley Scott Changed A Generation By Steven Kotler

|

The first words I spoke to her were a quote stolen, like so many other things in those days, from the movie Blade Runner. The year was 1986 and her name was Patricia. She was some kind of beautiful mutt: half-Japanese, half something else, maybe Polish. I met her in a bar in downtown Cleveland, but in 1986 downtown Cleveland was something of a misnomer. The city itself had burned to the ground during race riots in the sixties. Soon afterwards, insurance companies persuaded the government that a riot was "an act of God" and "an act of God" was not covered under their traditional policies. For this reason, the fifth largest metropolitan area in America became a dead zone, less of a physical place than a general bad mood. The Cleveland of my youth was not unlike the Los Angeles in Ridley Scott's film - a place from which everyone who could afford to had long since fled.

|

That the bar where I met Patricia was situated in the center of this downtown detritus should tell you a thing or two about the bar and a thing or two about the kind of people who crossed a wasteland to get a drink there. The reggae historian Michael Thomas once wrote that in Jamaica the Rastas say "I and I, meaning you and me, meaning we're all in it together." In Cleveland, subculture spoke a slightly different language, but the implications were the same. I met Patricia because she walked across a crowded room and stopped directly in front of me and took my hand in hers. These implications also meant that this was a period of time when you could walk up to a complete stranger and take their hand and not bother with hello.

|

Instead, Patricia asked how I was. So I told her. "I want more life, fucker" was what I told her. "I want more life, fucker" was the Blade Runner quote. It's what replicant Roy Batty said to his inventor, Eldon Tyrell, early on in the film. Certainly, "I want more life, fucker" was both pretentious claptrap and an almost entirely inappropriate thing to say to a young woman who had just bothered to try and make my acquaintance. But this too was part of our common language. For a small chunk of a generation quoting Blade Runner was just about the only form of prayer we knew. When I quoted the movie to her, she responded in kind. I said, "I want more life, fucker." She said, "Is this to be an empathy test?"

So did we find new life together in the off world colonies? We found something alright, gone now, like - as the film says - tears in the rain. What I remember clearest was our meeting over those quotes. There wasn't much to hang onto in those days, Blade Runner often felt like most of it. It was the movie that changed my life at a time I didn't think it was possible for a movie, or anything else for that matter, to change my life. I saw it not in the theater, but on video, sometime around my 22nd year. It struck hard. Within a few months I had seen it forty times, within a year over a hundred.

|

What was it? It was the fact that I grew up in Cleveland, that I grew up around freaks and weirdos, a pariah panoply stuck in the interment camp that was the American Midwest before MTV made the American Midwest safe for pariahs. But Blade Runner had made it feel different. The film was a swan song for the outsider. The hero was a failure at life, who found new hope in - of all things - forbidden robot love. The bad guy, Roy Batty, wasn't bad, he just wanted more: more hope, more love, more future. He wanted what everyone I knew wanted and he was prepared to do something we hadn't even thought of: take that new life by force.

Now there was an idea with some merit.

|

The movie was pure dystopia, and it was about triumph in dystopia. Clearly, the world was a broken place, Blade Runner was the film that let an entire generation know that you could pick up the pieces of the 20th Century and rebuild a future where dreams were still possible, even if everything around those dreams was rank. We didn't have a word for cyberpunk back then. We hadn't heard of William Gibson or Bruce Sterling. We didn't understand what was coming, the internet, the end of the cold war, the rise of feudal corporations, the blurring of borders. But we had some dread sense of what was in store and Ridley Scott confirmed our hunch.

What set Blade Runner further apart was that it was a film willing to ask a new type of philosophical question. What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to love a machine? How many generations away are we from the point at which there will have been so much globe-trotting and DNA mixing that race will stop being a meaningful way of distinguishing anyone from anyone - and what does it mean when that happens? What does it mean when nature becomes a rare commodity? When robots are sentient does robotics become a form of slavery? What is emotion? What is reality? How do we define consciousness? What is the difference between real memory and artificial memory? Over three decades have passed and these are all still pertinent questions, but at the time of the film's release these were astoundingly radical ideas.

|

And Scott didn't present them as pointless pondering. When Sean Young's Rachel says to Harrison Ford's Deckard, "I'm not in the business, I am the business," the truth was that we were all the business. Blade Runner wasn't just about some fanciful notions of tomorrow, it was about the natural evolution of the species. Here was a future that wasn't just coming, here was a future that was already gunning for us. "Quite an experience to live in fear," says Roy Batty, "that's what it is to be a slave." In those years, everyone I knew felt that way, myself included. This train had already left the station. Scott was saying out loud to us what we instinctually felt inside. No matter which direction we chose, it didn't really matter. The world according to Blade Runner was what was next. It wasn't a question of if, it was merely a question of when.

|

Certainly, some of this was abetted by the inadvertent consequence of technological advancement. The film was released in 1982. While the first home video machines went wide in 1975 - when the Japanese got involved - they didn't hit the middle of America until the mid-eighties. This meant that at the same time we were getting our very first video rental stores, those same stores were stocking Blade Runner. For film freaks this was the zero hour of liberation, suddenly free from the whims of the few theater owners who bothered to reprise cult classics, we could rewind and rewatch with impunity. I was not the only person I knew who hand wrote a version of the script, one play-pause-rewind moment after another.

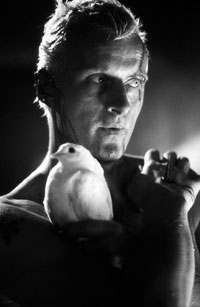

Certainly, some of this were the characters themselves. Harrison Ford was the antihero's antihero: "They didn't advertise for killers in the paper. That was my job. Ex-cop. Ex-blade runner. Ex killer." Rutger Hauer was among the greatest mythic characters ever created - and the lucky one gifted with one of film's legendary codas: "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe possible. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die." The Cleveland favorite was Edward James Olmos. He played Gaff, a half-Japanese, half-Mexican, origami-folding cholo pimp of a cop. Everybody I knew, knew somebody just like that guy. It was also Gaff's line: "Too bad she won't live, then again who does," that became Cleveland relationship slang for the end is near.

|

But it wasn't just Cleveland, the flick's vernacular spread wide. In Chicago I saw a mohawked rocker square off against a local jock. Before throwing the first punch, the rocker shouted the Blade Runner battle cry: "My mother, I'll tell you about my mother." Not long after the Revolting Cocks released a song called "Attack Ships on Fire." White Zombie followed that with "More Human Than Human." I said: "I want more life, fucker." Pop Will Eat Itself gave us "Wake Up Time To Die." Both Gary Newman and The Stranglers shortened it to "Time To Die." Warren Zevon based his entire Transverse City album on the film. And these are only a scant few examples. There are hundreds of others. She said: "Is this to be an empathy test." It was, and remains, a damn good answer.

|

Click images to view larger versions.