Articles

Heads Up, It's A Ray Turner Interview! by Stephen Jared

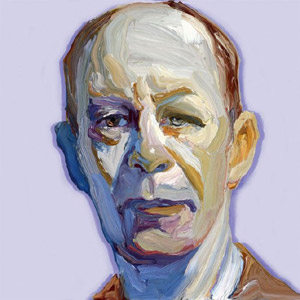

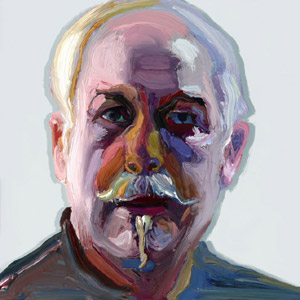

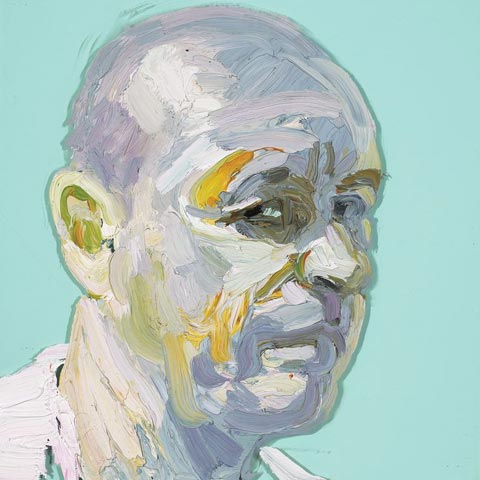

Throughout our lives we probably look at faces more than anything else. When we see spouses, parents, children, friends, co-workers plus strangers on the streets, in the shopping malls, at airports, we see a lot of faces. Yet how closely do we look? If it's a showing of Ray Turner's painted faces we look closely. We look for personality, history, commonality, understanding, and his subjects stare back at us, as if seeking the same. An illusion is created. We're engaged by what's familiar yet we're looking at heavy globs of paint.

|

Ray could've enhanced the illusion by painting photo-realistic portraits but that's not the direction he chose. The portraits are painterly, thickly brushed. They're not sculptural; nevertheless, the rich texture has expressive value.

There's not a second needed to determine the medium at work. The paintings are heavy, caked, squeezed-from-tube-to-surface thick, and with Ray's Population work, you're not just looking at the painting; the painting is looking at you.

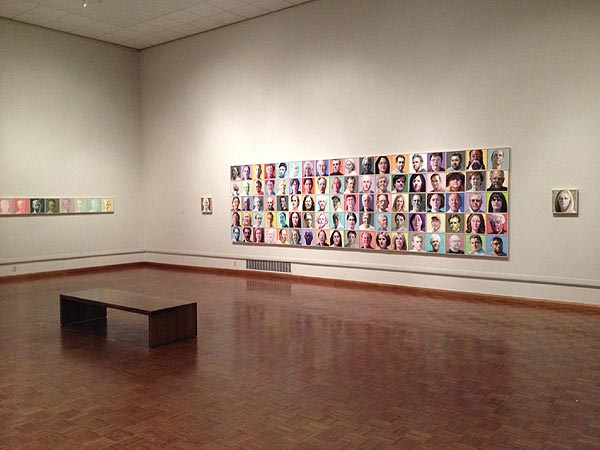

The Population series is visually stunning. It's also thought provoking. When people stare at us, especially a group of people at the same time, and say nothing, it's natural to assume they've got questions, right? What do they want to know? What questions are common among a population? Is it too much to suggest Ray's work asks questions that have forever been at the core of our existence? Who are we? What are we doing here?

Ray began Population in 2007. The exhibition has been in museums across the country. Hundreds of portraits make up the traveling show, each painted on 12-inch squares of glass, which are then displayed on a color field grid that becomes their background. Each exhibit is mounted with new portraits inclusive of people from within the visited communities. People in Akron become added subjects to the Akron exhibit. The idea is repeated in Wichita, Tacoma, and on and on.

|

He arrived in Pasadena from Tacoma in 1982 to study at The Art Center College of Design. After graduating, he taught at The Art Center for a dozen years or so while painting. During this time he became friends with fellow painter Richard Bunkall. As Richard became debilitated with Lou Gehrig's Disease, Ray helped him continue working. After Richard died, Ray and Richard's widow, Sally Storch, remained close and eventually married.

What inspired you to want to be an artist?

A football player friend of mine was copying pictures out of Sports Illustrated. He could really draw. I was intrigued as heck by it. I asked how he got started and he said, 'you should draw an egg,' and so I put an egg on a piece of paper and after about three tries I drew a pretty convincing egg. That was my sophomore year in college. And then I took a beginning drawing class my junior year. It was toward the end of the year because I transferred from a school I was playing football for, and the art instructor took me under his wing, and said, 'I don't know how much longer you plan on playing sports but you got something you can do for the rest of your life here.' I was just mystified by it. It was absolutely pulling rabbits out of a hat all the time, thinking 'this is magic, this is so much fun, it's intoxicating.'

Did the ideas behind Population evolve over time or did you start with the fully realized idea?

I don't think anyone ever has a fully realized idea on anything. If they do, they're regurgitating something and it's boring, and I think that would be an awful place to be. You're learning something all the time by doing. I think that organic progression is what makes the work more interesting each day. If I'm doing a portrait it's based on a photograph and so it's a specific person, and I want to represent them, but the last thing I'm really interested in is their likeness. I'm more interested in the paint, and how I put the paint down, the application of things. I'm looking at the photograph and I have this experience where there's this dialogue or intimacy that's really quite profound. That's a discovery element. I'm taking one two-dimensional surface and moving it to another two-dimensional surface. I'm creating this illusion of that person, and you wouldn't expect there to be that intimacy but there's in fact more intimacy on some level for me because it's projected so I'm really doing a self portrait in a lot of ways. I'm taking my personal human experiences and projecting them onto this other person, and imagining what they are, and I have this sense like I know who they are, and it feels like there's this life there that is other than a flat surface that happens to represent this person. So, I'm more interested in that. I'm more interested in the dialogue, discovery.

|

Do you prepare for a portrait with studies beforehand?

No.

Do you lay down some kind of foundation that captures the likeness and build from there, or do you start with a loaded brush?

Ninety-five percent of the time I just load the glass. If I'm painting portraits I'm just loading the paint on the glass. I'll often just squeeze the paint right onto the glass. I may put a big puddle of paint from the palette to the glass as well, mix it all together, move it around. If you look at thirty portraits, you see 'Oh, he's not really just painting eyes like that, a nose like this.' I'm really experimenting.

One tends to look at a completed picture, especially a portrait, and think of it as having been more calculated but it's more chaotic.

Maybe not chaotic, but reactive. I'm creating a problem for myself by the way I pick the paint up and put it on. I'm creating a problem, but I'm also creating a new mark, and out of that mark the surface is either working or it isn't, which then forces me to make another mark. So it's that layering or mark-making and going over the top of one and the other that allows the whole experiment to take place. All those happy accidents happen because I'm creating an arena for it to happen. I want it to happen. I do things to take myself off balance. When I was teaching, I used to make the analogy that you can be a good skier by carefully going down the mountain. I'd rather be the wet skier who chances taking a fall. I'm doing the same thing with paint. I want to be off balance, do something I've not done before.

|

When I first saw your work I thought of Frank Auerbach. Then I thought you were nothing like Auerbach. What do you make of the comparison? Are you a fan of Auerbach?

I'm definitely a fan. I have a whole bunch of painters in my head, and in my heart. They're people I really admire. What I'm doing now is taking from this whole amalgam of ideas and history, different people, and making my work from it. I'm very much aware of all those people who are heroes, people elevated to that point of a master. What I encourage myself to do is get out of the way, just make the work. Don't contrive. Best to say to yourself, 'I don't know what I'm doing.' That's pretty much true anyway (laughs). Honestly, I don't think we know beans about beans. The great thing about the whole process is that it is a process.

When you feel a work is finished is it a revelation that it's a great painting or is it more like Dr. Frankenstein feeling 'It's alive!'.

That's a good analogy, the Frankenstein thing. That feels more right to me. I guess the other part of the question is, 'How do you know when its finished?' That's an elusive proposition - I don't think they ever are finished on some level. Sometimes there's an exhibit and it's finished because I brought it to that place. That's the life that it has right now. I could've maybe put another screw in his neck or added another finger. I see it a week later or two weeks later or a couple of years later and I think I wish it wasn't alive. I'd like to kill that thing (laughs).

Sometimes works become more endearing because of their imperfections.

I think that's absolutely true. With painting there's something you can't quite put your finger on. There's something rich about it that takes you somewhere else.

Obviously, there's a lot of spontaneity involved, and a sort of figure-it-out-as-you-go approach in making one of these. At the same time, this painting (I point at one of his self portraits), I don't think it was something you could have done at eighteen.

Right. No way.

|

So then there is some amount of technique, some academic understanding of what needs to be done, and I'm wondering if you can put a ratio on how much is intuitive, maybe playing around, and how much is based on experience thus far.

I think it comes down to the mileage you've attained, the amount of travail. It takes time. It takes the adversity of stumbling, trying to find your way. If you decide to do representational work it's going to take a period of time before you can do it. I think the same is true for abstract work. You can't do magic from beginning to end. Although I think Van Gogh did and Basquiat did. Everything they touched had integrity. I was on a scholarship committee and the students would apply for a scholarship and I'd see these portfolios from the beginning when they first came in, and then third or fourth semester. Some of the drawings in the entrance portfolios were better than the drawings they did later. They'd gotten more facility but they lost that discovery thing that rang so true. There's something true about making a mark that you don't know as opposed to making a mark that you do know. But you have to go through it enough to recognize it. It can be an elusive thing because you're trying to do something new while at the same time you can't forget that you know all this other stuff. Picasso said it took four years to paint like Raphael and a lifetime to paint like a child. I think that's the balancing act all the time.

What did your parents do? Were they supportive? Were you artistic as a kid?

My senior year in High School, in order to graduate, I had to take an art class, and I remember becoming enamored by it. We had to do a clay thing and a gouache. And then later I met that guy doing the Sports Illustrated.

And your parents?

They were okay. They were supportive enough. They weren't the kind of parents to be too involved, so as far as me being an artist, it didn't matter to them.

Have you known a lot of painters who never caught on, or have you seen the truly great talents discovered?

|

I've seen a terrific amount of success in general. Maybe it's the era we're in. I've seen a few artists who I was surprised they didn't stick with it. For the most part, people I've been in contact with have been pretty successful overall. There've been some stratosphere successes too where they're catapulted into a whole other arena. I don't think you can do that without the talent. But there's definitely a road to acclaim that happens because of who you know and where you are and all those things. I think that has an effect on how one is perceived. Based on that perception and acclaim a wind in their sails will manifest itself in sort of a fanned ember, and they get bigger and bigger. But to get there you have to have something special.

I think for most people artistic expression doesn't come naturally. Most artists go through an awkward phase, even a pretentious phase, where they're maybe too imitative of their idols. For some though, it's very natural. Those are usually the ones who grew up around it. How was it for you? Did you immediately feel comfortable as an artist?

I don't feel comfortable yet as an artist. And, if someone's being honest, I don't think anyone's comfortable in any shape as a human being. You might be more comfortable because you have enough money to do whatever you want to do, but everybody's uncomfortable. I think I'm still imitative. I'm still looking. I'm still taking things in and moving them around the way I want to move them around. I think I'm less that way than I was. If you look at the work of Anselm Kiefer, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, it's fresh, different, and it's their work but then you look at Chaim Soutine in relation to Auerbach, and you look at found object people from the turn of the last century in relation to Rauschenberg. It's based on derivations but not necessarily imitation.

Tell me about the process of coming up with the background?

The main thing is that it's an installation-based body of work. I wanted to go into the museum and change the museum at every venue. How you incorporate the background with the figure is something where there are a whole bunch of possibilities. Because you've already established the figure, the background can be a lot of different things. So, I thought that if I paint opaquely on glass I can change the background as many times as I want. So, this time it's on mint green, next time it can be on purple, it can be on orange or whatever, and the whole thing will take on a different appearance, and I can work with some of the color theories I love. So I can go from warm to cool, light to dark, do triads, do harmonies, do complimentary systems and all that with a grid that goes on the wall. The way this all started was being in a paint store. I love all those swatches. I just love looking at that. I love paint in every form and shape. And so I thought, 'What if there's a head on every one of those, and it was in a big installation?' Also, to make it unique to each museum, I incorporate new portraits from that community so their uncelebrated can be celebrated.

If you were racing around the world and only had a few minutes to spend in each of the great museums, whose work would you rush to?

Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter, Sean Scully, Francis Bacon, Rembrandt, Van Gogh.

Do you give a lot of thought to career strategy? Do you just follow your heart and do what you want?

|

I taught full time for years. My first sabbatical I took a full year at half pay and that spoiled the heck out of me. I wanted to cut myself free of teaching and just work. And I thought, 'well, I just have to muster more courage.' I apply more courage in my work, and consistently it's okay, I keep going. My arms are open wider in terms of appreciating other people's work, and my arms are open wider in terms of making work for myself. A lot of great art is made out of insecurity and striving and struggle. I struggle with what I'm doing, and why I'm doing it. I want to have significance with my work. I don't want to be in this not to do great work. The times when I don't feel I'm battling that is when I'm painting. If I'm doing the work I don't care what anybody thinks, I don't care what I think. That's the best part; I'm out of the way. I'm just picking up that brush and making stuff.

The possibilities for what a painting could be widened enormously between the 19th and 20th centuries. Do you wish you were around when these developments occurred? Do you envy those who were involved in so much that was shockingly new?

I think things are more widely open now than even then, and there's more of a platform, and more of a willing embrace. I'm envious of anybody who does good work but that's a great feeling for me because my utter respect is there. I couldn't pay a higher compliment than wishing I'd done it. I think this is a great period of time to do art. The visual library is so immense.

You had a museum showing with Wayne Thiebaud? Did he come down for the show? Did you meet him? What was he like?

He's a good guy, nice family man, loves tennis. He's probably in his early 90s.

I love his work, and once read an interview with him where he said he chose the pies and cakes as subjects because he loved them as a kid. I thought that was terrific, and interesting because so many of our adult choices seem rooted in childhood.

His was the first painting I ever saw in my life where I thought, 'Oh, wow.' And then when I came to Art Center they had a poster of his deserts. They were prints for sale in the student store. So the museum show I had was kind of a full circle for me, or whatever. I love Thiebaud.

Aside from his obvious courage and dedication to his art, tell me about Richard.

I was going to move to New York but I took Richard's painting class and the first day he had this dry wit, so smart, he had this great sense of humor, he'd just grin with his eyes. We became fast friends. Everybody loved him. I found him to be the most courageous person I ever knew. He was remarkable. He had a gift, a singular vision, everything was kind of this motion toward this body of work that had this thread where you could see it was all his work. We were pretty good friends. Well, we were best friends, that's what we were.

Ray Turner - Self Portrait Ray Turner - Self Portrait |

Click images to view larger versions